Kelly Tapia-Chuning

Kelly Tapìa-Chuning (b. 1997) is a mixed-race Chicana artist of Indigenous descent from southern Utah currently based in Detroit, MI. In 2020, she received a BFA in Studio Arts from Southern Utah University; and is pursuing an MFA in Fiber at Cranbrook Academy of Art, where she was awarded a Gilbert Fellowship.

-

Kelly Tapia-Chuning (b. 1997, California) is a mixed Xicana artist of Indígena descent, living and working between Utah and Montana. Her multidisciplinary practice involves genealogical and historical research, textile appropriation and deconstruction, and large-scale needle felting. Through her work, Tapia-Chuning critically examines histories of assimilation and the power dynamics related to cultural and racial identity, gender, and language.

Tapia-Chuning received an MFA in Fiber from Cranbrook Academy of Art and was awarded a Gilbert Fellowship. She is the 2023 recipient of CAA’s Professional Development Fellow in Visual Arts Award. Tapia-Chuning’s work has been included in exhibitions with the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, The Shepherd (MI), Kimball Art Center (UT), GAVLAK (LA), Cranbrook Art Museum (MI), Eric Firestone Gallery (NYC), Onna House (NY & FL), among others. Upcoming exhibitions include the 18th International Triennial of Textile in Łódź. Tapia-Chuning was an artist in residence at Stove Works (TN), and her work has been featured in Artnet News, Southwest Contemporary, Surface Mag, and Juxtapoz Art & Culture Magazine. Tapia-Chuning’s work is held in numerous private and public collections across the US, including Cranbrook Art Museum, The Bunker Artspace, Onna House, the State of Utah Alice Merrill Horne Art Collection, and the Southern Utah Museum of Art.

-

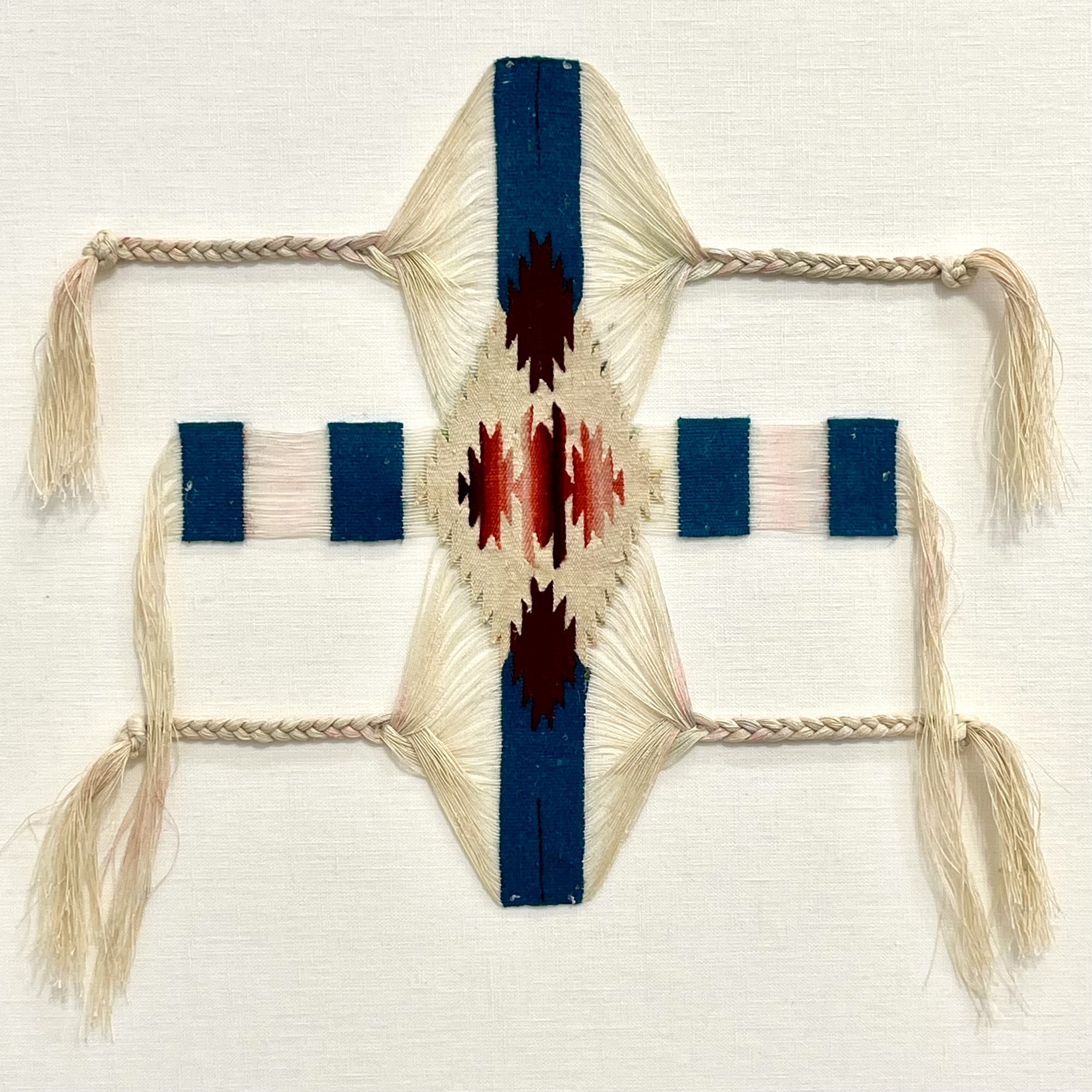

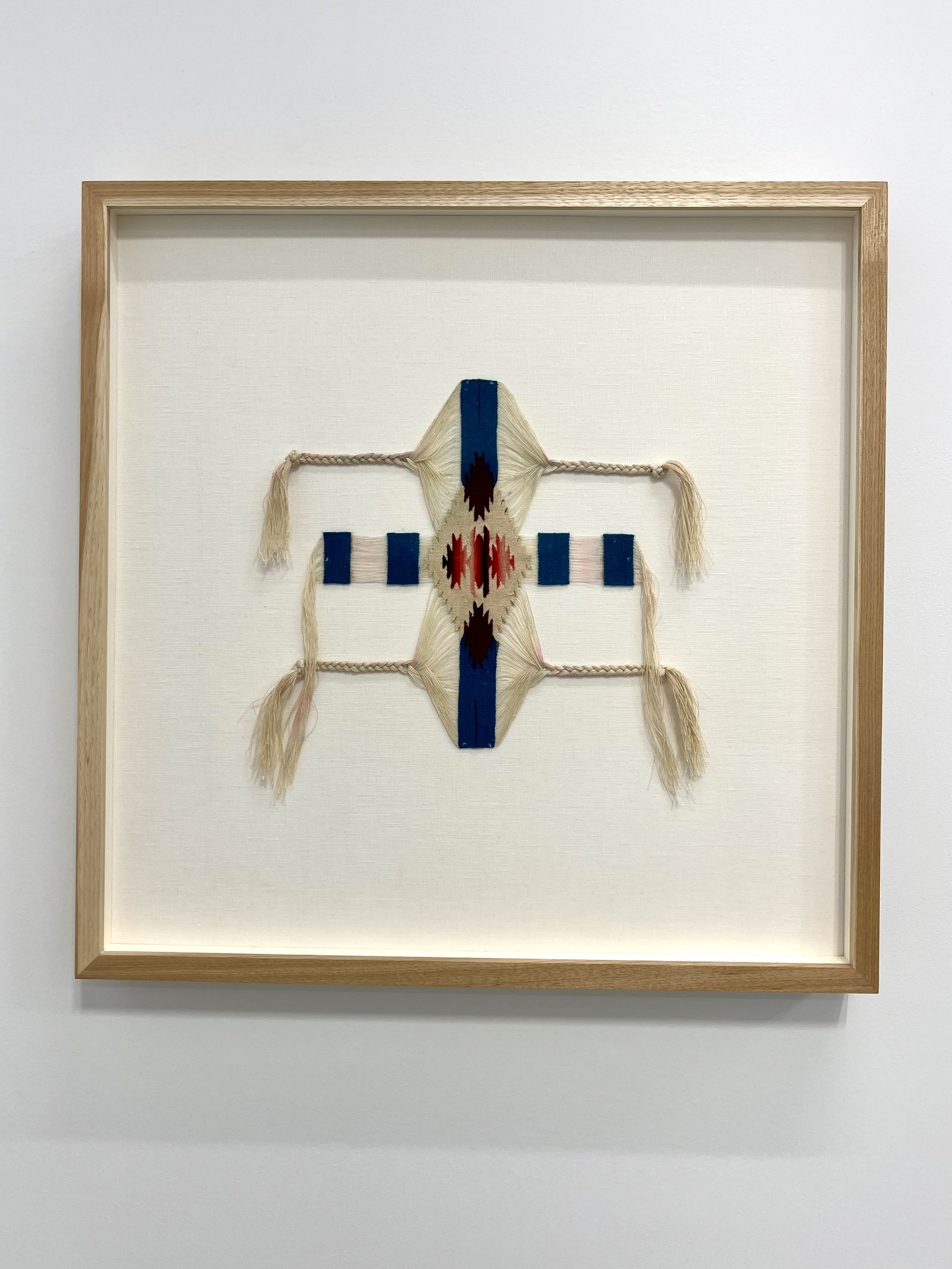

In post-revolutionary Mexico, the visual representation of mixture in the serape promoted the notion of a homogeneous national “mestizo” identity. As an act of decolonization, dismantling the serape has become a vehicle for honoring my ancestors, re-centering the narrative around ancestral knowledge and Indigeneity. Through the dismantling process, the textile becomes vulnerable, reflecting my notions of identity and selfhood. Removing the weft reveals its imprint, unfurling a history that cannot be erased. The narrative, however, can be re-centered and re-contextualized.

By utilizing the serape—an iconic symbol of Mexican patriotism with both colonial European and Indigenous origins—I aim to acknowledge history while reimagining the future. Through the deconstruction of the serape and its history, I challenge the system of assimilation that has impacted not only my family but many others as a consequence of colonization. My work examines this traditional “Mexican” textile to prompt questions and inquiry, reframing the conventional narratives of a dominant visual representation. By removing parts of the serape, I signal a dismantling of the systems within colonial power structures.

In Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s text “Light in the Dark,” Anzaldúa describes the “process of falling apart” as a prerequisite for healing. Colonization disrupted my family’s ties to our Indigenous culture. I aim to restore those severed threads by deconstructing and reconstructing the serape. The work I create through ritual plays a part in my own becoming, with the viewer/audience acting as witnesses of this becoming.

Each piece is a site of tension, revealing personal and familial histories marked by colonial violence. My ancestors and living relatives have endured multiple waves of assimilation—first Hispanicized, then Anglicized—as a descendant of this violence, susto is the sickness that follows generationally. In Chicanx/a/o and Latinx/a/o communities, susto (meaning fright) refers to the ailment associated with a traumatic event that results in the soul’s departure from the body. This phenomenon is often linked to the violence and loss of land and culture due to colonization. In my work, dismantling the serape is an act of healing this generational susto.

My family’s history and lineage are complex, and I am the culmination of that assimilation and erasure. However, my work results from the re-rooting practices in which I participate. My practice critically examines how ‘mestizaje’ and assimilation have obscured individuality and ancestral knowledge through imperial-imposed representation, investigating the visual culture that emerged from colonization. My work aims to create new visual imagery to mend ancestral trauma and reconnect with cultures and familial histories long forgotten.

-

Instagram: @kelly_chuning

Remembrance, dismantled serape, 23 x 23 inches, 2025, $3,500 (with frame)

Abundance, dismantled serape, 2025, $3,500 (with frame)

Remembrance, dismantled serape, 23 x 23 inches, 2025, $3,500 (with frame)

Fire Wakes/When healing began, dismantled serape, copper nails, 15 x 29 inches, 2025, $5,000

Fire Wakes/When healing began (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 15 x 29 inches, 2025, $5,000

Fire Wakes/When healing began (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 15 x 29 inches, 2025, $5,000

Fire Wakes/When healing began (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 15 x 29 inches, 2025, $5,000

self portrait as serape, a study of halves, dismantled serape, copper nails 20.5 x 22 inches, 2023, $5,500

self portrait as serape, a study of halves (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails 20.5 x 22 inches, 2023, $5,500

when the Sun touches the Earth, dismantled serape, copper nails, 23 x 28 inches, 2025, $6,000

when the Sun touches the Earth (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 23 x 28 inches, 2025, $6,000

when the Sun touches the Earth (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 23 x 28 inches, 2025, $6,000

when the Sun touches the Earth (detail), dismantled serape, copper nails, 23 x 28 inches, 2025, $6,000

noche del sol carmesí (evening of the crimson sun), dismantled serape (Mexican blanket), copper nails, 32 x 74 inches, 2023, SOLD

Mestiza (a woman of Spanish and Indigenous descent), latex interior paint on vintage serape, 46 x 89 inches, 2022, SOLD

Vendida, latex interior paint on vintage serape, 19 x 44 inches, 2022, SOLD

A Study of Scale, dismantled serape, copper nails, 9.5 x 18.5 inches, 2023, SOLD

Guera (slang for a white girl), latex interior paint on vintage serape, 45 x 93 inches, 2022, $5,100

Loteria Cards, 2019, linocut on rag paper composition: 7.5” x 11” sheet: 14.5” x 18” (edition of 4), $200 per print, $2,000 for one complete set of 16 prints